The funeral of former Sinn Féin MLA Mickey Brady took place in Newry on Friday, as family, friends and political colleagues were among the large crowd of mourners who gathered to pay tribute to a man widely described as a “people’s champion”.

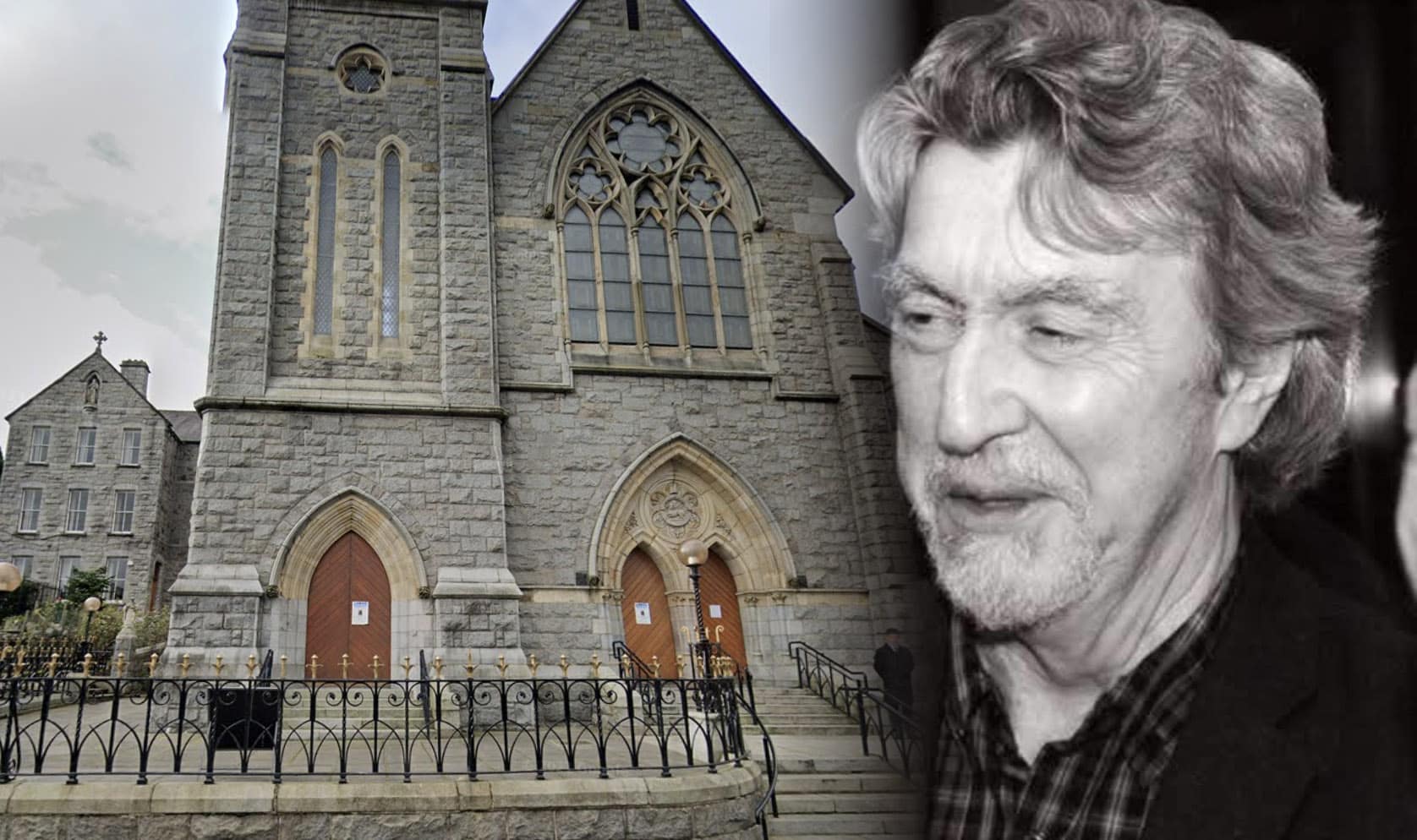

Large crowds lined the streets as the cortege made its way to the Dominican Church in Newry, draped in the Irish tricolour; Mickey was a proud Irish republican, a devout Dominican Catholic and a man especially proud of his Newry – his Ballybot – roots.

Among those in attendance were First Minister Michelle O’Neill and Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald, alongside party colleagues, elected representatives and community activists from across the North and beyond.

The Requiem Mass was celebrated by Father Gerard Tremer, who told mourners he had grown up as both a neighbour and a friend of Mickey Brady, describing him as a man whose life had been defined by compassion, humour and unwavering commitment to others.

During the service, deeply personal items were brought to the altar to reflect Mr Brady’s life and passions. These included photographs of Mickey and the wider Brady family taken at a recent wedding, a squash medal he had won, his trademark hat, a mandolin symbolising his love of music, and writings from Bobby Sands, reflecting the moment that shaped his life’s work. Mickey began working in welfare rights on the very day Bobby Sands died.

Mickey’s daughter, Saoirse, delivered a deeply personal tribute laced with humour – something her dad would have approved of.

She described him as a proud former altar boy, a lifelong Dominican Catholic, a Down supporter “despite what he told the people of South Armagh during election years”, and a devoted fan of Manchester United and Celtic.

“He was a caring husband, a loving and dedicated father, a devoted and doting grandfather,” she said, adding that he was also a skilled squash player, an “alright” mandolin player, a daredevil hang-glider and a captivating storyteller.

Saoirse spoke of the overwhelming outpouring of support since her father’s passing, saying it reflected the depth of his kindness and humility.

“Someone said to me that the two Newry men most in demand were Joe Hughes in the Credit Union and Mickey Brady,” she said. “That’s because Mickey never said no to anyone.”

She told mourners how even while critically ill in ICU, her father’s phone continued to buzz with people asking for help with forms and appeals. “You couldn’t get any more Mickey Brady than that,” she said.

“As we all know, Mickey was a proud Ballybot man. He refused to describe himself as anything else. He was born at home in Kiln Street, delivered by his Granny Finnegan and Mrs Kinney, who, by all accounts, were three sheets to the wind at the time. We always said that explained a lot.”

Born to Sally and Willie Brady, Mickey was the youngest of five, his late brother Jim and him bookending the three girls, Mary, Theresa and Lillian.

“Apparently, he was lucky to survive childhood after Lillian dropped him on his head as a baby and then pushed him down the stairs in his toy car,” Saoirse added.

“But they all doted on him, and none more so than his late mother, Sally, famous in her own right for being one of the oldest women in Ireland. No matter where in the world my father travelled, he rang my Nanny Brady every single night before she went to bed until she passed at the age of 107.

“Both his parents were a huge influence on his life. His father’s stories of travelling to Armagh as a child to see Michael Collins make his election address in 1921 clearly planted a seed. My Granda Brady, an electrician by trade from Markethill, unfortunately didn’t pass down any practical or DIY skills to my dad.

“At the age of 18, my dad left Newry to study at John Moores University in Liverpool. The story goes, when he was walking home alone from a house party in 1971, Mary Kane from Newry recognised what we affectionately call dad’s distinctive rain walk and shouted his name.

“I’m sure anyone who’s ever canvassed with Mickey would recognise that walk – head down, hunched shoulders, launching himself forward. That was the first time he met Rose Boyce, a four-foot-11 Geordie who was with Mary that night. Despite being an awkward, gangly student who had only ever gone to all-boys’ schools and could barely speak to a girl, she agreed to go out with him when he first brought her home in Newcastle.

“They married in 1975 and moved back to Newry. As we all know, 1981 was an important year in Mickey’s life. Not only did he welcome his first child into the world – me – he also became a poacher-turned-gamekeeper when he established the Welfare Rights Centre.

“Over the last few days, we met so many people who either worked in Bridge Street or Ballybot House with my dad that we reckoned not only was he keeping the local economy afloat with the amount of money generated by ensuring people accessed their rightful benefits, but he was employing half of Newry as well at one point or another.”

Saoirse recalled the passing of her mother – Mickey’s first wife – in 1989.

“My dad became a single parent, left with three small children; myself, Michael and Sean. His own mother and mother-in-law, as well as his sisters, were pillars of support, but he was always there for us and insisted on doing all the important things alone. We knew it was a difficult time for him. He called it his Leonard Cohen phase.

“But we knew he turned a corner when he started playing Van Morrison’s Wavelength album on repeat in the car. It turns out the reason why was because it was playing the night he met Caroline in 1990 in Squires Bar. Fate clearly intervened to ensure he was in the right place at the right time that night.

“Their wedding in 1991, in my Aunt Mary and Uncle George’s garden, still forms part of Newry folklore, and so many people have mentioned that fondly over recent days. When they married, we gained a new big brother in Lewis, and in 1992, Niall arrived – the final piece in the jigsaw, as my dad called him.

“Skipping forward, and as you’ve already heard, Mickey entered politics in 2007, but what you might not know is that not only did the people of Newry and Armagh gain a giant, but Nanny Brady’s nightly novenas were finally answered when he cut his hair after a decades-long argument – so thanks, Brian Tumilty.

“Working with Sinn Féin, not only did he get to continue to make a real difference in the lives of so many, he got to travel to places he never dreamt of going, and he loved every minute of it. And it was clear the love and respect that his Sinn Féin colleagues, friends and family had for him, but never more so than in the last few days, when they stood in the wind and rain and supported us every step of the way in this difficult journey.”

In retirement, she said, Mickey remained as active as ever, volunteering, travelling and continuing to campaign for causes close to his heart, including Palestine.

Even in death, she noted, he had raised almost £5,000 for Medical Aid for Palestinians.

Reflecting on her father’s legacy, she said: “His name is always met with a smile and a story. The words kind, gentle, non-judgemental, witty and legend come up time and time again.”

Ending her tribute, she said: “It’s a running joke in our family that my dad ended every speech he ever made with tiocfaidh ár lá, even all of our wedding speeches. Even in my last conversation with him, just over a week ago, we talked about how he hoped to see a united Ireland for all, where everyone was welcome and equality was paramount… today, my father’s day has come. Tiocfaidh ár lá.”

Also paying a heartfelt tribute was Infrastructure Minister and Newry and Armagh MLA Liz Kimmins, who described Mickey as “an ordinary man who did extraordinary things for the people”.

“A name so familiar in many homes across Newry and its surrounding areas, a saviour to families for decades through the darkest and most difficult times,” she said.

Ms Kimmins said Mickey gave people hope when they had “very little left”, putting food on tables when cupboards were bare and acting as “the voice of the voiceless” for more than 50 years.

She recalled how, with his trademark denims and long hair, Mr Brady embarked on his welfare rights work in 1981, becoming the first Welfare Rights Officer of his kind in the North.

“Office hours meant nothing to Mickey,” she said. “No matter where or when you met him with a problem, his generosity of time ensured no one was turned away.”

Even after retiring, she said, Mickey continued to fill out benefits forms and assist people in the weeks before his death.

Ms Kimmins spoke of his move into elected politics as a “natural transition” for a committed socialist and republican, recalling his time as an MLA at Stormont and later as an MP at Westminster, where he worked alongside figures such as Jeremy Corbyn in pursuit of social justice and equality.

Despite holding senior political office, she said, Mickey never lost touch with grassroots activism.

“Whether it was a weekend advice clinic, a leaflet drop, an election canvas or a community coffee morning, Mickey would be there,” she said.

She also paid tribute to his humour, mischief and legendary storytelling, saying even political opponents found it hard not to be drawn to his warmth and wit.

“Above all, Mickey was a family man,” she added. “To Newry, he was our Ballybot boy and working-class hero. To his family, he was a husband, father, grandfather, brother and uncle.”

Concluding and fighting back tears, she said: “Slán go fóill mo chara. Mickey Brady, the people’s champion.”

Mickey was laid to rest afterwards in Monkshill Cemetery. May he rest in peace.